This is a new interview series on machine intelligence companies. First up is Beagle, which uses machine learning to help non-lawyers navigate complex contracts.

Few things are more daunting than legal documents.

Who has the time to research and try to understand all the technical terms, linguistic complications, and mind-numbing legalese? Or the money to pay someone to deal with all those things every time they have to work with a contract?

Many people don’t have either, and so they end up agreeing to terms that they never even knew about.

Beagle was founded to help those people. It automatically scans contracts, identifies some of the most important parts, and categorizes everything to make it easily searchable.

Since its founding, the company has been named one of the most innovative Canadian startups, been featured at SXSW, and participated in the Microsoft Ventures Accelerator, making it the first Canadian-based startup to do so.

ThinkApps recently interviewed Cian O’Sullivan, the founder and “top dog” at Beagle, to talk about how the company uses machine learning to continually improve its users’ experiences.

[Editor’s note: The interview questions and responses below have been edited for clarity and length.]

What’s your role at Beagle? What does that position entail?

I am the founder, the creator of the concept of Beagle. The title I gave myself is “Top Dog.”

My day is eclectic. The way I would describe being the CEO of a startup is that you have 10,000 balls in the air at any given time, and six of them aren’t allowed to drop, but you can only catch three. It’s a constant juggling act.

I spend my day moving the needle on strategies and making sure we are investing our time in the right way. When you are a small startup, you move ahead in about 20 different ways all at the same time, but everything has to be moving in the same direction.

What did you do prior to Beagle?

I did a lot of self-taught computer things, and I ended up being a network engineer. Then I went to law school, and I tried to bridge my IT skills with my legal training.

I took my New York state bar exam and realized pretty quickly that I didn’t want to be a lawyer. But I ended up doing a lot of work with contracts — on everything from mergers and acquisitions to contract negotiations — and whenever people found out I did that, they’d end up asking me for help with their own contracts.

One weekend, a friend asked me to look at a contract that his company had to evaluate by the following Monday. It ended up being a $15 million project. So while I was kind of cursing and swearing at him under my breath, I decided I should look at this problem in a different way, and the concept of a “quick look” really hit me.

If you give 10 lawyers the same contract for 10 minutes and ask them to highlight the most important parts, they’ll all come up with the same thing. So I decided to automate the task, to give people an idea of what a contract says without them having to worry too much about it or to ruin their friend’s weekend by asking them to take a look at it.

How did you teach Beagle to understand legalese?

Depending on the way you look at it, this looks like it could be unachievable. Like, there’s no possible way this could be handled.

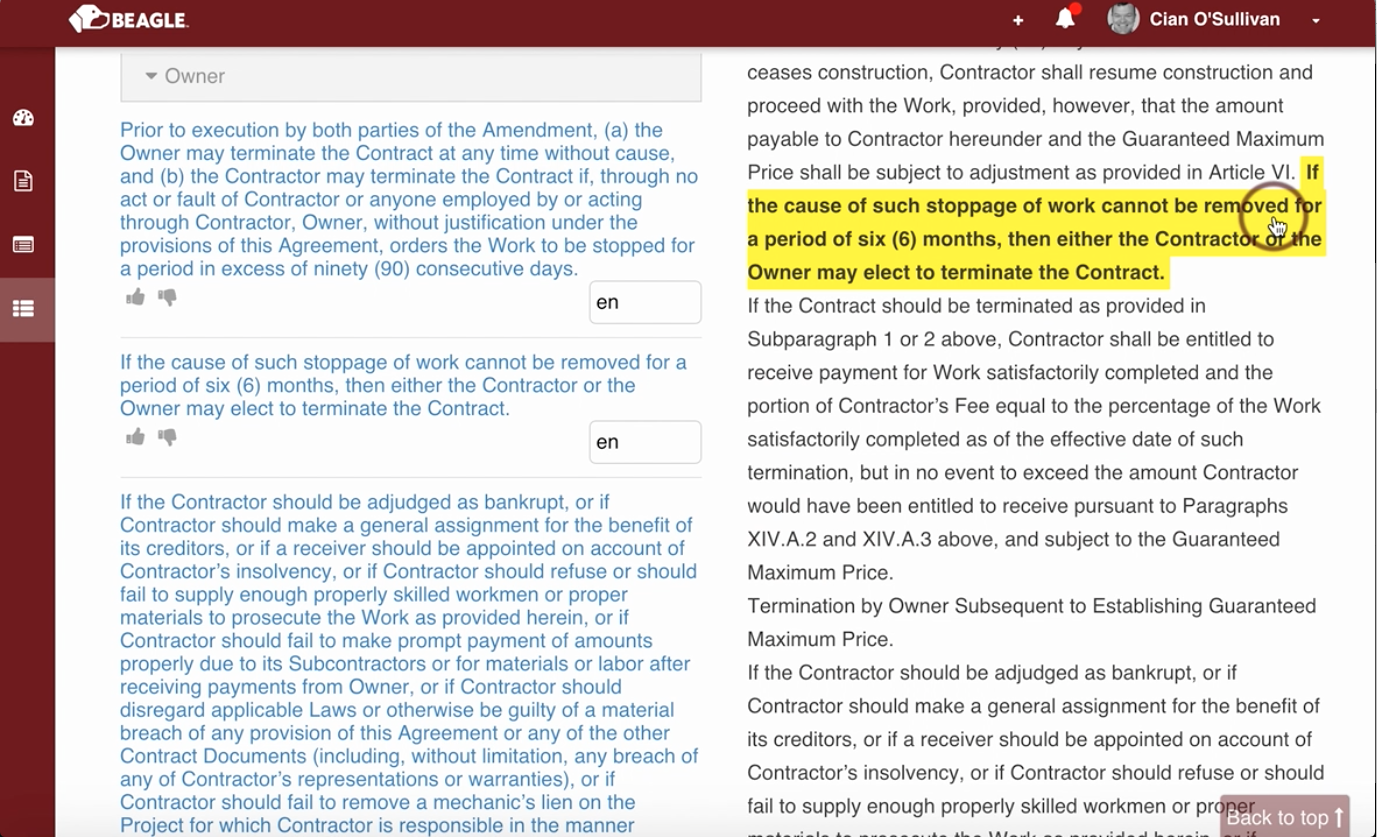

The way we do it is, we say, let’s take the concept of a contract and break it into categories of interest. When you think about it, the most important things you want to know about a contract are: who’s it between, who’s responsible for what, how can you get out of it, and who’s on the hook if things go wrong?

Now depending on the agreement type, you are going to need to know certain types of other information. So we pull out the things that are applicable to a particular category. That’s first. And if we do that, we give people 80 percent of the information they want. But where do they get the other 20 percent?

We have a tool in our system that is able to categorize things and allow you to search for things within those categories. Once you have that, the system now starts to learn.

It says, okay, I have enough information to be able to start to learn what you’re looking for individually, and as I start to see a pattern in that, I will know to search for that stuff for you. This is where the machine learning comes in, and it’s so transparent that the user doesn’t even realize that it’s happening.

How and what does Beagle learn? At what rate does it continue to improve?

Most people are gonna get the benefit of the prime system that we provide. The 80 percent. It’s up to the user to get the other 20 percent in whatever creative way they want.

A lot of users just worry about the 80 percent; they don’t try to train it themselves. But we can get results with just eight samples of data. So if they had eight clauses in one particular contract that actually met certain criteria, our system would look at that and see if it can compute with a reasonable probability the chance of detecting that going forward.

What’s interesting about machine learning is that as the system gets smarter, it doesn’t always look like it’s getting smarter to the average user.

Say a user finds 10 items. When they upload a new contract, Beagle identifies clauses it thinks falls into one of those categories. The user can then say yes, that’s right, or no, it’s not.

If they say no, that actually might be enough important information for Beagle to realize that the way it had done its original calculations needs to be completely restructured. So now the accuracy rate might go down a little bit while it tries to learn where these new boundaries are.

You’re always saying yes it’s right, or no it’s not … it’s not a huge battle, but we treat it like one. And people don’t even realize they’re training Beagle in real-time.

Have customers been wary of trusting an AI to handle contracts that deeply affect their lives?

They certainly have. There’s a lot of pushback. And the number one reason why there’s pushback is that they don’t know something like this exists in the first place, and they don’t want to change the way they’re doing things because their old system works.

If we look at the way the vast majority of companies handle their contracts currently, they will agree, there have been times when they signed an agreement they shouldn’t have, or they didn’t have time to look at it as much as they should have.

Or they might think that the contract isn’t really important because they have a good relationship with the other party. And to some extent that is true: the contract is set up for when you have a divorce, not how you handle the marriage.

Beagle is more important when it comes to getting work or selling something to someone with public funds. That’s where it starts to get really interesting because organizations agree that is the biggest and riskiest area. Every single person I’ve talked to said they have lost money on the job because they did not understand the requirements.

So we do get a bit of pushback, and what we say is, we’re not replacing your due diligence. That’s not what we’re doing. What we’re doing is providing you with a tool to make your due diligence process hugely more efficient.

I once showed a demo to a guy running structured steel companies who wasn’t a computer user. He stood up, did a little bit of search, and then looked up at me and said, “You just saved me a week’s worth of time.”

We’re certainly not a replacement for due diligence. What we’re doing is empowering you as a business owner to figure things out within minutes instead of hours or even days of work.

What is Beagle’s role within the legal tech community?

The technology in legal as it relates to other industries is very immature. For instance, legal technology is probably 15 years behind financial technology. Ten years ago you would have never thought you could do your income taxes online, and now you can.

So legal technology is still way behind, but the community is recognizing that and saying we can shave 5 or 6 or 10 years off development if we make sure that we’re collaborating.

Stanford University has put together a program between their legal department and their computer science department to create a legal informatics initiative called CodeX.

There is a very traditional high academic look at how you deal with legal information. So the purpose of CodeX is to try to bring that back down and make it industry relevant and be able to connect it to the legal students at Stanford but also the community as a whole — the general potential consumer of all types of legal services.

For CodeX, I’m an evangelist and also a networker in terms of trying to tie the companies together and making sure that we’re having all of those necessary discussions.

There’s a second organization that I’m part of called LegalX, which is focused purely on legal tech startups. It’s a global initiative that’s starting out of Toronto and is focused on understanding where those legal startups are coming from and being able to help facilitate getting them in front of big law firms or big companies.

It just so happens that there are a lot of legal tech companies in Ontario, CA, where we’re based. We definitely consider ourselves at the epicenter of that whole legal technology community that LegalX is trying to put together.

So these are the kind of initiatives — the more academic focus from Stanford CodeX and the more business, pragmatic focus from LegalX — that we are early members of. By surrounding ourselves with the right community, we ensure that we’re looking at the market and the approaches and the strategy in the most effective way.

Do you plan to remain focused on contracts, or will you expand to other difficult documents?

Long-term, yes, we’ll use artificial intelligence to be able to analyze narratives that should be objective. Legal language should be objectively written because, if you and I have an agreement and both of us depart our relevant companies, our replacements will be able to come in and figure out what we both intended.

You also see that in the medical and engineering sectors. There has to be a uniform method of communication between professionals or across the industry.

But still, the average person might not know what’s going on. That’s exactly where methodology that is able to process specialized objective narrative comes in. And in some cases, Beagle might even be able to translate documents so lay people can better understand them.

If you saw a radiology report saying there was a crack in your distal phalanx, for example, you’d be able to translate that to say, yeah, you’ve got a broken toe. We’d be able to do that because we have a corpus of data and understand how things are written and represented.

That’s the kind of stuff we’re working on in the background, but it’s really a three-to-five year play. It all comes down to time, cost, and scope.

If we had a boatload of resources and the right people, you could see it a little bit sooner. But at its core, Beagle is about accessibility and about providing transparent access to the information in front of you that might be hard to navigate.

What’s the most exciting trend in machine learning from Beagle’s perspective?

One of the things we’re trying to be really aggressive about is the concept of being able to use small pieces of data. You’ve got all this talk about big data. Big data, big data, big data. But what about small data?

Small data is a bundle of information that an individual should be able to process and handle. Contracts fall into that definition.

When we talk about machine learning, there’s so much emphasis on having massive quantities of data and using it to train. We want to do that with small data. That’s actually a lot harder.

Anyone can turn around and run a million equations on a bunch of data and say, this is what the outcome is going to be. It’s actually really tricky when you have small amounts of data.

We use machine learning to make sure that an individual will see a benefit. We’re not talking about an organization or huge governments; the stuff we do benefits the individual end-user.

What advances in machine learning have most benefitted Beagle?

The only way that we’re able to do this right now is twofold.

Number one is that there’s an incredibly transparent academic community about standards techniques and libraries available. This means we’re not in a position where we’d have to write our own algorithms.

Even 10 years ago, some of this stuff would have been very difficult. So we’re keeping our ear to that, and we’re able to experiment with a lot of things in a very, very short period of time.

The second positive is the ease of infrastructure. We can run off Google, Azure, and Amazon Web Services — and we actually use all three of them. We don’t have to focus on our own data centers, which makes us lean and allows us to really focus on the data science.

Are there any limitations on machine learning Beagle would like to see removed?

While the scientific community is very transparent, there’s been a lot of discovery from a proprietary perspective that hasn’t been shared, and some of the licensing models that some of the creators want make it extraordinarily difficult to be able to leverage.

Another thing that’s disappointing for us in one way is that the legal work with respect to applying artificial intelligence and machine learning to contracts or legal narrative is limited. Very little work has been done by others on that.

That forces us have to come up with a lot of the solutions. But, on the positive side, that shows we are trailblazers hitting the market at the right time.

How serious a threat do you consider machine learning initiatives from large companies?

Most of those large companies have built massive engines to deal with massive amounts of data that you as an individual company can leverage, but have to put in resources. And when you’re using their engine, they’re able to compute and take the data you’re providing and use it for their own purposes. But they are not focused on the individual contributor or end-user.

We’re doing a pilot with one of the world’s largest auto manufacturers in Germany, and they asked that exact question. My answer was that we are specialists at understanding how small pieces of data can affect people, and that we are focused on empowering individual end-users. So that helps.

But, on the positive side, these big companies help consumers understand that machine learning and artificial intelligence can improve their lives. It’s almost like they’re saying it’s OK for people to give us their permission to help solve their problems.

So we’re able to benefit from the fact that we aren’t creating something people haven’t heard of; we’re just applying it in a different way.

Stay tuned for more interviews with machine intelligence companies that are harnessing the power of machine learning and artificial intelligence in innovative ways.