Before he was the VP of Growth at Facebook, Alex Schultz was one of the few people in the world who transitioned from a career in physics to marketing.

Like many origin stories, his interest in marketing was driven by a lack of money. Specifically, Schultz got into online marketing because he needed to pay for college. By the 1990s, he became fascinated by the world of SEO back when “it was a really, really easy skill to learn.”

He learned to program because he was tired of being the nerdiest person in physics class and taught himself the skill through the creation of a cocktail site. His skills turned his project into the largest cocktail site in the UK.

Then he fell into growth hacking before it even had a real name. In his mind it was just Internet marketing: “using whatever channel you can to get whatever output you want.” Schultz not only paid for college, but he also transitioned to the “dark side” (a.k.a. marketing for good).

He discussed the untamed beast that is growth during his lecture at Stanford University as part of Y Combinator president Sam Altman’s series on How to Start a Startup.

(For more startup advice, check out How to Start a Startup: The Book. It’s the ultimate reference guide to creating a successful tech startup.)

Pay Attention to Your Retention Curve

What do you think matters most for growth? Great products, customers, or word of mouth? It’s actually the culmination of all three: retention.

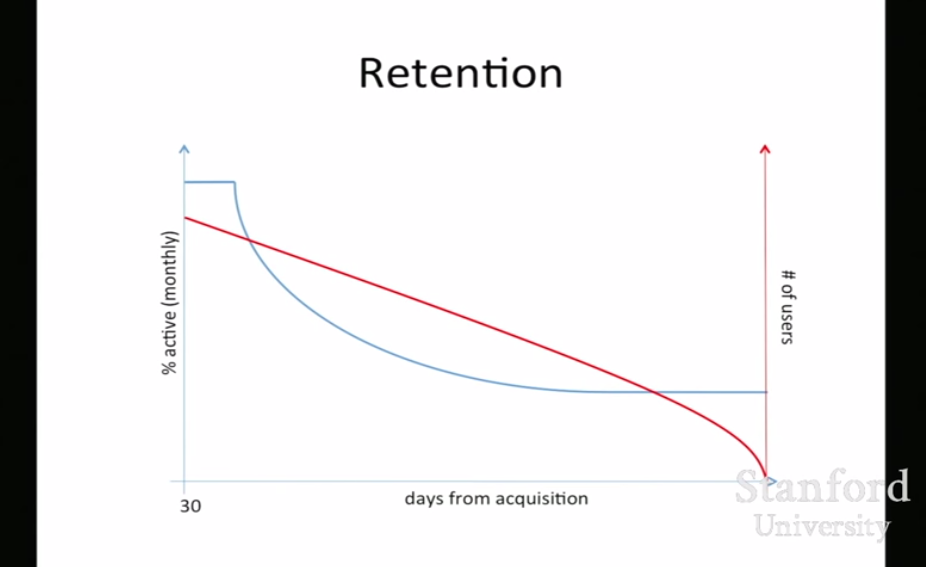

It’s a given that startups want to grow, so Schultz contends the most important graph that any founder can look at is a retention curve (see below).

If you plot the percentage of monthly active users versus the number of days from acquisition, you should end up with a retention curve that is asymptotic to a line parallel to the X-axis. That’s when you have a viable business.

Schultz explains that your next step is to see how many of your users have been using your product for one day. Ask yourself: What percentage of them are active monthly?

“100% for the first 30 days obviously, because monthly active, they also end up on one day,” he says. “But then you look at 31. Every single user on their 31st day after registration, what percentage of them are monthly active? Thirty-second day, thirty-third day, thirty-fourth day.”

Even if you only have 10,000 customers, you’re still going to get an idea of what this curve is going to look like for your product. You’re going to be able to tell if it’s asymptotic.

“If it doesn’t flatten out, don’t go into growth tactics. Don’t do virality. Don’t hire a growth hacker. Focus on getting product market fit,” Schultz advises. “If you don’t have a great product, there’s no point in executing more on growing it because it won’t grow.”

“[The] number one problem I’ve seen for startups is they don’t actually have product market fit when they think they do,” he adds.

What Does Good Retention Look Like?

Schultz says he gets pissed off when people ask him the above question because it’s so easy to figure out using dimensional reasoning.

He shared the story of Geoffrey Taylor, a British physicist who won the Nobel Prize. Just by looking at pictures of the atomic bomb, he figured out the power of the U.S. bomb. (Read this article if you want to learn exactly how Taylor did it.)

Dimensional reasoning involves looking at the dimensions that are involved in a problem to come to a solution. Taylor used dimensional reasoning to figure out what the power of the U.S. atomic bomb was, as well as the ratio of power between the Russian and American bombs. And he ended up revealing one of the top secrets that existed in the world at that time.

Figuring out the ratio of power between the Russian and U.S. atomic bombs is hard. Figuring out Facebook’s retention rate is not so hard.

There are approximately 2 billion people on the Internet (excluding China where Facebook is banned), and Facebook has around 1.3 billion active users. Divide the second number by the first to find out Facebook’s retention rate. It won’t give you the most accurate answer, but it’ll be close enough.

Your Retention Rate Depends on Your Vertical

Different verticals need different terminal retention rates for them to have successful businesses, according to Schultz.

“If you’re in ecommerce and your monthly active basis retention is close to 20% to 30% of your users, you’re going to do very well. If you’re on social media, and the first batch of people signing up to your product are not 80% retained, you’re not going to have a massive social media site,” Schultz explains.

Ask yourself: Who out there is comparable? And am I anywhere close to what real success looks like in this vertical?

But, at the end of the day, no matter what vertical you’re in, “[r]etention comes from having a great idea, a great product to back up that idea, and great product market fit,” Schultz says.

Operating for Growth

Schultz says that startups shouldn’t have growth teams because the entire company should be focused on growth. The head of growth should be the CEO, acting as the north star for where the company wants to go.

For example, Mark Zuckerberg is Facebook’s north star because he’s always been focused on growth. In the early years of Facebook, many companies focused on their registered users. But Zuckerberg focused on monthly active users instead.

Schultz recounts that, when Zuckerberg talked about growth, he meant “everyone active on Facebook, not everyone signed up on Facebook” and that was the internal goal. “It was the number he made the whole world hold Facebook to, as a number that we cared about.”

Airbnb followed a similar model when it came to measuring growth. They’ve always benchmarked themselves against the number of nights booked compared to the largest hotel chains in the world.

The takeaway is that the metric for growth varies from company to company. What matters is that the CEO is focused on that metric, acting as the company’s north star.

“Let’s say you have awesome product market fit. You’ve built an ecommerce site, and you have 60% of people coming back every single month, and making a purchase from you, which would be absolutely fantastic. How do you then take that and say, ‘Now it’s time to scale.’ That’s where growth teams come in,” Schultz explains.

Importance of the Magic Moment

When you hear the term “magic moment,” you might think of a touching moment between a couple or this song. But there is another magic moment: when users first see value in your business.

The magic moment for Facebook? Schultz says it’s when people can see their friends. It’s that simple. The magic moment takes place when you first see that first picture of one of your friends on Facebook and you realize, “Oh my God, this is what this site is about!”

For Zuckerberg, that magic moment depended on getting people to 10 friends in 14 days. The most important thing in a social media site is connecting to your friends. Without that, you have a completely empty newsfeed and you’re not going to come back because you’ll never get any friends telling you about things you’re missing on the site.

Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, LinkedIn – they all pay attention to showing you the people you want to follow, connect to, send messages to, as quickly as possible, because that’s what matters. In a different vertical, eBay‘s magic moment is when you list an item on their platform and get paid.

You need to think about what the magic moment is for your product and get users connected to it as fast as possible. Then you can move up where that blue line (on the retention curve graph) becomes asymptotic. If you can connect people with what draws them to your site, then you can go from 60% retention to 70% retention easily, explains Schultz.

Schultz says that you get to that magic moment by “focusing on the marginal user – the one person who doesn’t get a notification in a given day, month, or year.” Building an awesome product is all about the power user. But when it comes to driving growth, you don’t need to worry about people who are already using your product.

Tactics for Virality

Sean Parker approaches virality in terms of three things: payload (how many people can you hit with any given viral blast), conversion rate, and frequency. These three factors give you a fundamental idea of how viral a product is.

Hotmail (now called Outlook) is “the canonical example of brilliant viral marketing,” according to Schultz.

When Hotmail first entered the email scene, people couldn’t get free email clients because they had to be tied to their ISP. Hotmail and a few other companies launched, and their users were able to access their mail from wherever they were.

Most of these email companies tried to get clients by spending tons of money on TV, billboard, and newspaper campaigns, but Hotmail couldn’t do that because they didn’t have a lot of funding. So they added a little link at the bottom of every email that said, “Sent from Hotmail. Get your free email here.”

Because Hotmail users were usually emailing just one person at a time, the payload was low. But the frequency was high because users were emailing the same people over and over. So those people were going to be hit one to three times per day, increasing impressions. And the conversion rate was also really high because people didn’t like being tied to their ISP email.

In the end, Hotmail became extremely viral because of its high frequency and high conversion rates.

Next Steps

If you’re interested in viral marketing and advertising, Schultz recommends reading Viral Loop by Adam Penenberg and Ogilvy on Advertising by David Ogilvy. You can also read a full transcript of Schultz’s lecture here.

Also, if you enjoyed this post, be sure to check out How to Start a Startup: The Book. It’s the ultimate reference guide to creating a successful tech startup.

Featured image of Alex Schultz was taken from the video of this lecture at Stanford University.